OLGA STOZHAR

January 28 – March 6, 2020

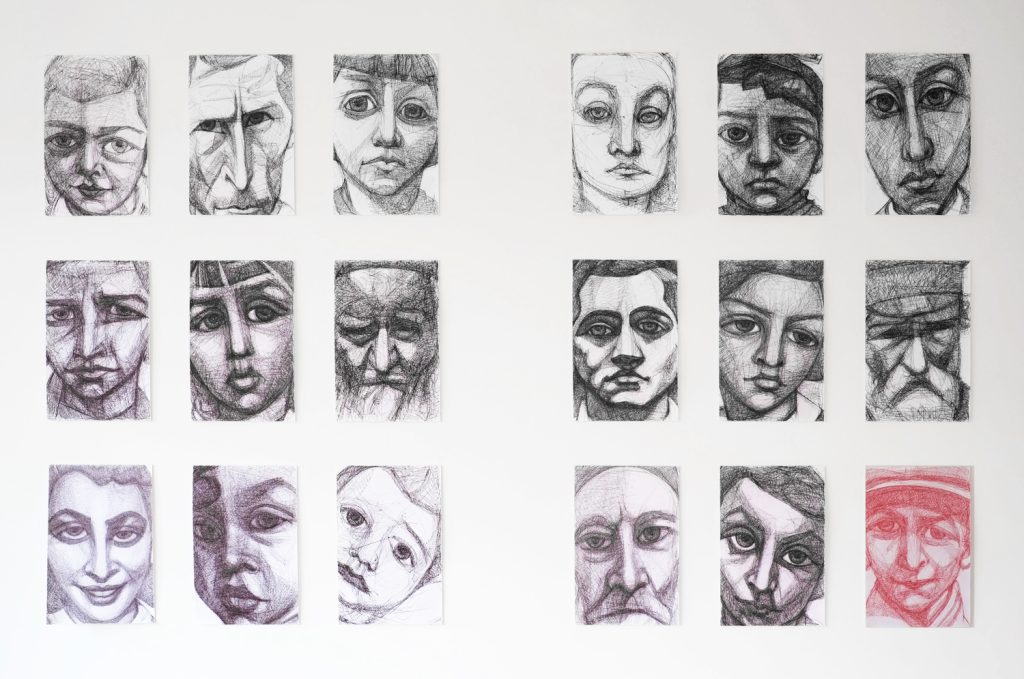

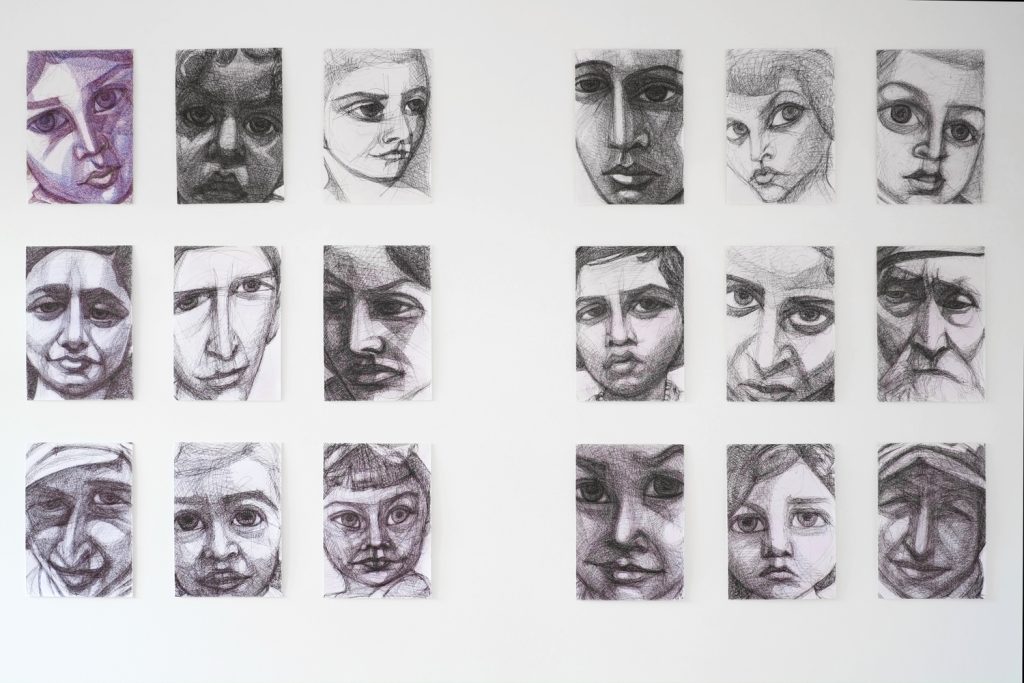

For the past three years, the Jewish-Russian artist Olga Stozhar has been working on a large-scale project that addresses a subjective history of remembrance and the artistic “revitalization” of the victims of National Socialism. The project is titled *“they are looking at us.”* Olga Stozhar uses photographs of victims who perished in concentration camps or during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. She draws these images from archives and existing documentation, using them as templates in an intense drawing process to bring the facial features of the victims to a different form of aliveness on A3-sized paper, using continuous lines in black, blue, or red ink.

This aliveness is driven by the artist’s electrifying, dynamic line, with which she deliberately deviates from classical drawing techniques. She does not use the line primarily to define volume or accentuate the characteristic features of a face. Rather, the line functions like a pendulum with a weight, used to gather momentum—allowing her, through sweeping motions, to trace an extremely complex path across the drawing surface. This path always leads her to the edges of the paper and back to various densified zones that arise over the course of the work. This rich and intricate drawing process evokes an empathetic connection with the Other and their emotional state. In this sense, one can speak of her drawing instrument as a direct extension of her own emotions in relation to the murdered Other.

Stozhar uses a fine, circling line—one that always remains a line. Even in the most intense condensations or erratically jagged forms, it is still the single line that traces a path toward an unforeseeable destination. Sometimes it is pressed harder, sometimes more softly onto the paper, but it remains the same thin line throughout. She does not employ multiplied or mechanical lines such as hatching. Her line allows for density, tangling, a tight interweaving with itself—but also moments of isolation within the emptiness of space. Its path on the paper is defined by dynamic progression and expansion, as well as countless reversals. The paper’s space is explored differently in each drawing. At times, areas become so densely filled with line that the white of the paper disappears; other areas remain open, where the paper reveals itself as a bright white field. Yet this white and black have nothing to do with light and shadow. In Olga Stozhar’s drawing world, there is, remarkably, no light and no shadow. One could say instead that it is a world beyond our natural world—a world of speaking spirits or a realm of souls. Nothing is narrated in her drawing world; rather, everything is concentrated on elemental human expression.

The faces are much larger in scale than a real human face. And yet, they do not appear monumental. The focus on the interplay of lines reveals only human expression—not isolated features of the face. This focus on expression keeps us at a distance, allowing us to perceive the faces as equal, not enlarged. The visibly material physicality and energy of the line, paired with the fragile delicacy and thinness of the paper, make human vulnerability and imprint all the more evident.

The dialogue between the drawn densities and the blank areas on the white surface of the paper causes a continual shift in our perception. One cannot determine whether meaning lies in fullness or in emptiness. It is precisely this oscillation that lends Stozhar’s approach to the murdered an appropriateness—through an open attribution of significance—because we, as the survivors, must find our own access anew with each individual drawing.

When viewed sequentially, as if in a book, the richness and diversity of the human face and the life inscribed within it become apparent. But when the faces are seen as part of carefully arranged clusters in the exhibition, a different and paradoxical experience emerges. In the fullness of their interplay, the loss inflicted on humanity through these murders becomes evident. Yet, at the same time—and this is a striking experience—a relationship forms between these people. They begin to speak with one another. Because this dialogue within each presentation block plays such an important role, Olga Stozhar devoted much time to the installation itself. Her aim is to show warmth and love—everything opposite to violence, death, cruelty, and injustice.

As a dialogical network structure, Stozhar has chosen a rhythm of three, creating a natural tension between centering and decentralization, between middle and outer figures. At the same time, a vertical and horizontal connection arises between the faces due to the consistent spacing. This opens up a more complex field of possibilities, as formal qualities of individual drawings can leap from one sheet to the next. Each face is shaped by the treatment of mouth, nose, eyes, and ears—along with the accompanying element of hair. The way the eyes relate to each other, how a nose sets itself between them and leads toward a mouth, how the mouth gives the nostrils a sense of closure or opening through the curve of the lips—this is always rendered differently.

And yet, since Olga Stozhar’s line never describes a single sensory organ but integrates it into a network of connecting lines from which it grows, these connecting lines can also initiate a conversation with the neighboring face. Materialities such as hair or specific forms are not imitated—everything is geared toward connection. Only the paths of connection themselves can vary greatly in their formal design.

One organ, however, stands out despite all the movement in the line and becomes a place of stillness within the dynamic accents of the surface: the eyes. They serve as a focal point, fastening themselves onto us as viewers, and awaiting from us an answer to humanity’s unanswered questions.

Can art grapple with this catastrophe of humanity? Adorno’s dictum still echoes: that to write a poem after the horror of Auschwitz would be barbaric. This dictum certainly cannot be answered with artistic realism—for the murdered cannot be called back to life in this way. Olga Stozhar’s response to this challenge is twofold: she replaces realism with a drawing process that is not directed at outward appearance, and she excludes the horror itself. Instead, she begins at the core of the human—the individual expression. Her act of revitalization remains entirely bound to the artistic process.

Stozhar creates for herself the free line, which seems to flow out from within her and, in an empathetic immersion into the Other, charts its course. The line enters an open process that must be different for each person, every time. Stozhar has not devised a fixed strategy, but instead continually engages in an open search for the Other. In an apparently erratic process, she allows her line free rein. At times, she darkens the white space of the drawing sheet to such an extent that she pushes the paper to the brink of its own fibrous limits. The unfamiliar person is to be created in a single drawing gesture. No details are chiseled out; everything is directed toward revealing the complexity of the person, which emerges in the connections, in the interplay of density and emptiness, and expresses itself therein through its particular vitality.

Olga Stozhar’s approach avoids any totalizing portrayal of the victims’ state of being. Instead, she establishes a new connection between them. Her delicate, dynamic, and fine line allows the faces to speak in such different ways that a sense of humanity emerges between them—one that was utterly absent in the perpetrators. Stozhar’s formal device—the unrestrained drawing pen—sets a dialectic in motion that liberates the victims in their own being, condenses this being into a polyphonic chorus of highly individual voices, and thereby creates a sense of togetherness that, in a paradoxical way, celebrates human diversity in the face of their destruction and confronts us, the descendants, with the question of humanity.

Text: Rolf Hengesbach

Installation Views