Markus Willeke

November 20, 2022 – January 27, 2023

To shatter against a hard surface, to meet death and lose one’s form? Life is a complex process of many components interacting to form a whole. When is it alive, when is it dead? The exhibition title ‘Ground’ chosen by Markus Willeke might be surprising and confusing as a basis for comparison. What does a dead bird on the ground have to do with paint bursting on a solid surface? In both cases, a movement has found an abrupt end: the movement of a living being and an artistic movement. At the same time, however, an extreme contrast is also created. We are not dealing with a real bird, but with its depiction. In it, the difference between life and death must be meticulously and sovereignly worked out through the artistic handling of paint. In the other case, does an artistic will to create express itself with self-destructive means (flinging paint), thereby bringing about its own death (or life after death) in the randomness (and beauty) of the result? Every painting must cope with the paradox that pictorial liveliness can only be bought through solidified paint.

Destruction has been a leitmotif in art for the last hundred years. In Willeke’s work, it is coupled with a reflective view of its aesthetic aspects: what formal designs are appropriate to the theme? Destruction can bring forth beauty in the power of unfolding new forms and sounds. Our consciousness must adjust, be ready to leave behind visual habits and make reversals, but at the same time reflect these reversals themselves. Willeke engages in his work with these reversals to extreme contrasts.

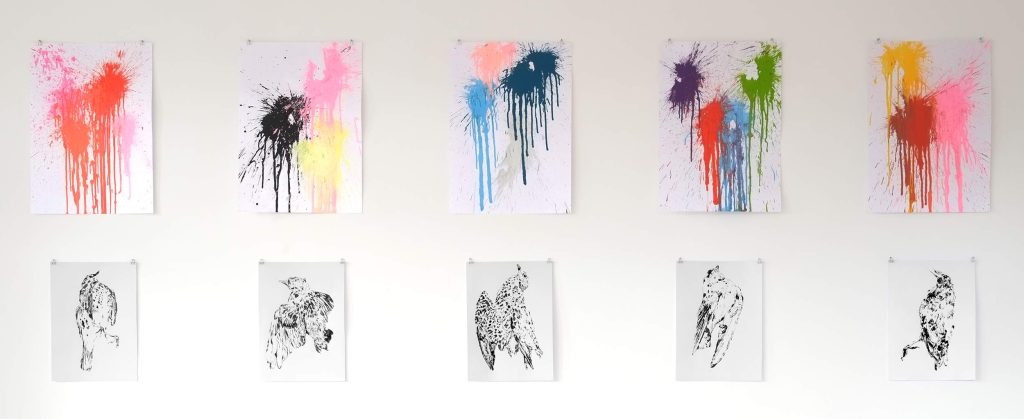

Birds have two forms of appearance: a resting, physically compact form with folded wings close to the body, and a moving one with wings spread out. These two poles merge in their opposition in the dead state because the body loses its compact form: the wings more or less spread, the head no longer directed straight but slightly turned to the side or tilted back, and the plumage disheveled. The physical coherence disintegrates into individual islands that, no longer held by a center, seem to strive towards the edge. That an invisible physical interior as a center is capable of initiating and perpetuating the strong movements of the periphery, the wings, is still conceivable, but fading.

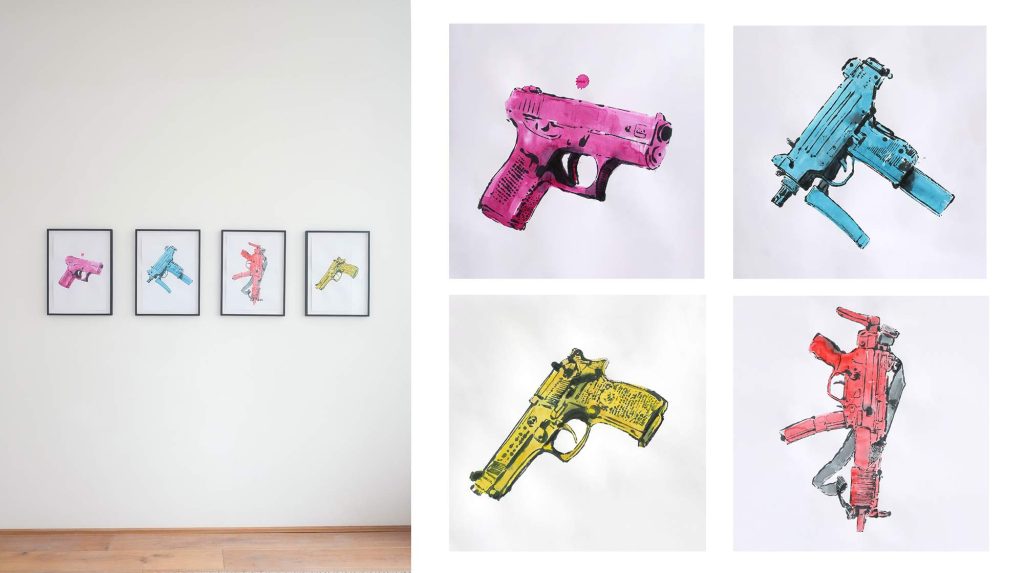

The splattered paint bombs resemble feathers on which violence has been inflicted, disintegrating into a chaotic mix of components. Here, paint is no longer the fine chiseling of the world in its manifold differences; instead, paint becomes a projectile, a blatant overlay of objects and surfaces, destruction of views in the imprinting of an alienated view, expression of political agitation.

Birds have a unique view of the world, wide-ranging orientation possibilities that no other beings possess. They can spontaneously break away from the ground and embark on entirely different local contexts and span them. On the other hand, their death is dramatically evident: a plunge into the abyss. If we apply such perspectives to humans, we would talk about freedom and its flip side. The ‘freedom’ of birds is threatened by us humans. Often, they crash into our buildings or technological devices, deceived by the illusions we erect.

The dead birds by Markus Willeke are presented to us in portrait format, each a web of islands, rivulets, finest lines, and variably shimmering flows of black or anthracite color. Although there are original dead birds as model templates, Willeke’s pictorial result does not make them appear as drawings or models. The difference between body parts is leveled. The eyes, for example, are nothing more than a spot among others. Various paint application techniques, such as monotype, linocut, and screen printing, are used. Willeke manages to reverse these techniques in his images so that the impression is not of a subjective drawing executed by a human hand. Rather, the paint seems to act autonomously, finding paths of self-representation in its spread on the surface.

The evaluation of ‘freedom’ and ‘political agitation’ has played an increasingly significant role in the examination of our social self-understanding in public discourse over the past nearly three years. Who is allowed to die? Must the body remain intact? What intrusions are permissible on it? How may opposing opinions clash, color, and tarnish each other? These questions, while reflecting on the visual and thematic elements of Willeke’s work, also challenge us to consider broader societal issues and the implications of our interactions with and impact on the natural world.

A dead bird is not just a dead bird. The unvarnished, vulnerable display of a deceased being in public spaces is in itself a barb. For its immersion into the sphere of meaning (freedom, environmental destruction and change) that turns our coexistence into a divergence, and for it to condense into an aesthetic symbol, it is necessary that it receives an appropriate form. The bird must be able to unleash a force in its portrayal that makes it frightening, suffering in death, yet also alive; the painterly color must resurrect it from within itself.

Rolf Hengesbach