Axel Lieber

November 2, 2021 – January 28, 2022

Photos: Dirk Wüstenhagen

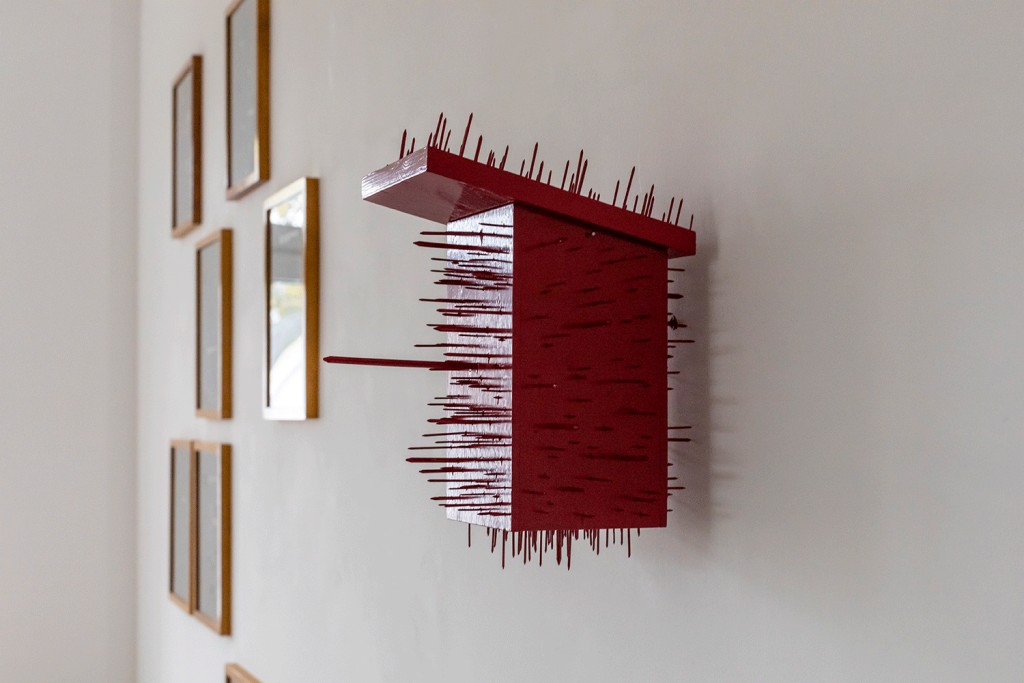

An evidence room is a secured space for storing evidence. Axel Lieber’s chamber cannot be entered but is visible from the outside. It resembles a rack in which the pieces of evidence are fitted. Evidence evokes a past event, are fragments and aspects of that event, and stimulate visualization and interpretation. They provide insight into the dimensions of the event regardless of whether it is pleasant or unpleasant to us. They expose, but the exposures are only visible in a skeletal form. They can get to the core of a matter, condense the event, but in doing so, they sometimes turn it upside down or invert it, so that the inside is turned out and the outside is questioned about its inside. They are something concrete, assign the event to individual areas, and lead to considerations of the general significance of the actions converging in the event.

Evidence pieces are objects, but their objecthood initially does not provide adequate clarification about their true character. The significance of them only becomes visible when their entanglement in actions is uncovered, and they inform us more precisely about these actions and visually illustrate them for us. From our familiarity with actions and our knowledge of the variety of possible actions, the correct reference of the object to this variety must be discerned, and the possibilities reduced to the decisive event.

If we transfer these considerations to the Lieberian concept of sculpture, it becomes immediately apparent that his works have little to do with a classical sculpture as an aesthetic formation of an object. The two central concepts of form invention and material design play only a subordinate role for him. Lieber’s works are also not adequately described as the adoption and transformation of things. Although he uses existing objects, his artistic interventions are not mere transformations but complete conversions of things into something else, where essential aspects of the object-like nature are reversed in favor of the relationship to human action and human events.

Lieber’s sculptures are sometimes also referred to as assemblages because they occasionally consist of a combination of objects. However, such an interpretation only emphasizes the original origin and the diversity of the objects but does not consider the sculptural work with regard to the newly emerged physical structure, the actions associated with it, and the poetic structures linked to it.

Another misinterpretation must be rejected: Axel Lieber comes from a generation of sculptors in which there was a strong movement to shape objects into models. Their intention is to reduce the diversity of our world to elementary ideas and striking clarity. However, despite outward appearances, Lieber’s concern is not object-like reduction, but transformation into a verbalizing space of meaning associations. Instead of petrifying into elementary formations, he wants to liquefy; instead of constructing aesthetic prototypes, he wants to disseminate sculptural inconspicuousness that breaks with rigid objectness and evokes human events as a dynamic structure. That is why Lieber’s sculptures usually have only a low weight. They prefer closeness to paper because thoughts can fly or float on it and are not bound to stone or metal.

An evidence room preserves the past. However, without our interpretative work, the objects are just stale fragments, bringing no vitality back into our world, and no human event in its bizarre diversity comes back to life. Lieber’s sculptures are not done justice if viewed as opposing objects that can be questioned about aesthetic qualities. His sculptural work consists of a disembodiment of things and their transformation into a new corporeality. The disembodiment is brought about by hollowing out and fragmenting, a work of the hands. In the German language, we have semantically preserved the closeness between hand and action. Hands are often the starting point for actions. Their secret or subliminal life, their indirect visibility, plays a central role in many of Lieber’s sculptures: in suggestions of movement, in form compressions, or as something hidden behind coverings, as in puppet play.

Lieber’s new corporeality sometimes appears as a remnant, as something shriveled, emaciated, stretched or elongated, tensed, as something nested or interlocked. However, these states do not stand on their own or represent an intended value. They must always be understood in such a way that in this transformation of things or these inversions, the human body forms the indispensable intermediary. With the human body comes movement, force, but at the same time also action and the shaping of the human living space. Our body is constantly occupied with considerations and planning to organize our life. This consists of a variety of actions, which can be generally interpreted as ordering, adjusting and setting up, inserting, arranging, collecting, making suitable or fitting, measuring, staying, giving oneself a hold, dressing, grasping, maintaining composure, giving oneself a frame or placing oneself in one, directing oneself, straightening up, setting up, creating space, laying down and picking up again, counting and telling, remembering, going inward, and so on.

Let us clarify this with an analogy to human language: Lieber transforms the previously classic substantival nature of sculpture into a verbalizing sculpture. This is a significant paradigm shift towards a different way of looking at sculpture. Because by focusing on human events, two fundamental questions come to the fore: Human events can take place in different ways. The modes of process are constantly being evaluated by applying standards to them. In all his works, Lieber raises questions about the right standard. Human events can not only be observed externally in their course but also viewed internally. In the internal perspective, we are interested in the motives and meanings with which we interpret the events. We draw these meanings from the extensive reservoir of our verbal attributions and the network we create with descriptions, within which we constantly make shifting adjustments. In Lieber’s sculptures, not only are activities evoked, but also our evaluation and interpretation possibilities.

Let us consider an initially completely inconspicuous sculpture: a limp ribbon hangs from a strut in the evidence room. The ribbon is a shoelace, on which small rings of fabric material are strung into a chain. The rings are the round, perforated fragments of the fabric of the eyelet strip of a sneaker, where the shoelace, with its pulling force, once did its job. No longer the horizontally stretched form of the sneaker, but the shoelace itself, like a “silken thread,” holds the object-like existence together. What once enclosed the foot and gave it support has dissolved. However, the force with which it was tightened, providing a secure fit and the possibility for a stable stance and firm footprint, is preserved. The ornamental form of the fabric has transformed into another ornamental form, into a chain that could gently lay around our neck, thereby turning the lower into the upper.

Lieber’s sculptures do not derive their appeal from the material body itself but from the exchange of bodies they suggest or propose, as well as from the shifting of meanings that emerge in the associative flow of the activities connected with them. Sometimes such a flow reminds one of childish fantasies that, in their overflowing richness of associations, do not yet feel constrained by the separation into isolated objects. However, to become free for this, a different kind of perception and mental contemplation is necessary than merely confronting an object. Lieber’s works demand a resonance in the rich space of human activity and action, while at the same time inviting an immersion into the poetic depth of the attributions of meaning to our actions with their motivational contexts. For this purpose, they allow us to penetrate into a deeper kind of engagement and view of the world of our human events beyond mere evidence.

Rolf Hengesbach